Meet the man who counterfeits the world's most famous diamonds

By PRI's The World, Bradley Campbell. January 03, 2014

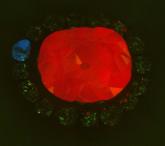

Photo Credit: John Nels Hatleberg

Hatleberg's replica of the Centenary Diamond

The best diamonds in the world contain mysteries. And years ago, John Hatleberg was unlocking the mystery of one of the best.

He stood in the outer vault of the Smithsonian with its then-curator John White. Both stared at the Hope Diamond, the largest blue diamond in the world. They took it off its display. Then, they turned off the lights.

“We took a short wave illumination, a short wave light,” he says. You probably know it as a black light.

“And for just about a minute, we let the stone soak up the photons of that wavelength.” All in the dark.

“What happened with the Hope Diamond, the most famous jewel in the world, it turned red,” Hatleberg says. It glowed like a hot coal.

The Hope Diamond emits a red phosphorescence after being bombarded with ultraviolet light.

Research at the Smithsonian suggests that, inside the Hope diamond, at the atomic level, the ultraviolet light causes interactions between trace boron and nitrogen impurities, which then give off the red phosphorescence.

Hatleberg offers his own, non-scientific reason: “The Hope Diamond is not only a 350-year-old cultural and historic icon. It’s also possessed.”

“I wouldn’t say Satanic," he says, laughing, "but I guess I just did. I’ve never said that before.”

If the Hope held a secret, Hatleberg knew other famous diamonds across the world could, too. But getting access to priceless gems is hard without a reason. So Hatleberg started down a path that turned him into one of the greatest legal counterfeiters of diamonds in the world.

Some say, the greatest.

“People have said that I’ve held more famous diamonds than anybody in history.”

Getting started

Hatleberg began his love affair with gems at age 10, in geology class. He saw his first crystal. It entranced him. So his mom signed him up for a gem-cutting class at a suburban recreation center. And that’s where he cut his first gem, an agate.

“I think they literally had some kind of box for me to stand on, so I could reach the wheels,” he recalls.

One class turned to two. Gems hooked him. He says a childhood love of magic tricks from the Top Hat Company in Elgin, Illinois, also played a part. For him, gems contain power, whether alchemical or simply magical.

“In terms of looking for some attraction, for the roots of my involvement with gems and minerals, which are unusual, I think that starts as a good base explanation,” he says.

Hatleberg's replica of the Hope Diamond.

He kept cutting gems from the fourth grade through college. His mom found an elderly man named Joe Touchette who offered to teach Hatleberg the finer skills of gem cutting. On Saturday mornings, Hatleberg would go over to Touchette's house and they would work on gems in his basement.

“The main thing I learned down there was patience.”

During that time he says he also haunted the Smithsonian. He’d spend his free time with its mineral collection. That turned into a summer job washing mineral specimens and labeling items of the collection. And after college at Wesleyan University, he came back to the place with an interesting proposition.

“I want[ed] to take the Hope Diamond out of its setting and make a mold of it, so that we can make chocolates.”

He wanted to give people a chance to get closer to the jewel.

“In a very democratic manner, you’d be giving them a piece of it.”

A piece they could eat. What's the phrase? Body of Christ given to you. Well, this was body of diamonds given to all.

So on December 5th 1988 — yes, he remembers the exact date — he made an RTV silicon mold of the Hope Diamond. He hasn’t stopped since.

The attraction

Ever since humans walked the Earth, they have been attracted to diamonds. European and Asian kings wore them into battle to make them feel invincible. Diamonds are prized across cultures — from the Koh-i-Noor Diamond at the Tower of London, to the Dresden Green diamond in Germany, to the Golden Jubilee in Thailand. But maybe it’s Shirely Bassey, of James Bond fame, who describes them best.

“Diamonds are forever," she sings in the famous hit. "They are all I need to please me. They can stimulate and tease me. They won’t leave in the night, have no fear that they might desert me.”

Diamonds are better than secret agents. They’re also stronger. They're one of the hardest materials produced by our planet. They’re objects of desire. Gifts of love.

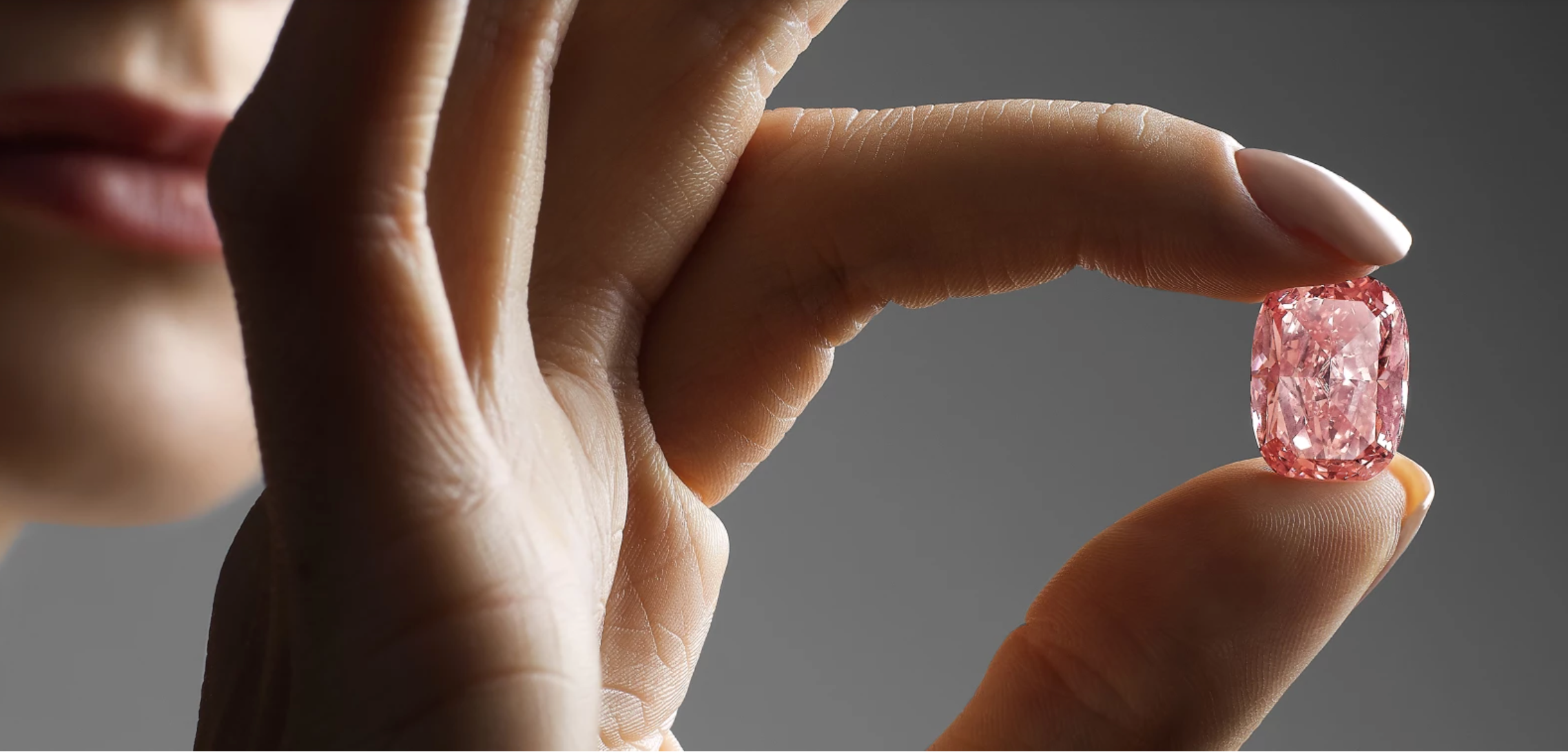

The best ones, determined by carat, cut, color, and clarity, can be extremely valuable. Take the Pink Star diamond — they all have names — which recently sold in Geneva for $83 million. Now, it's called the Pink Dream.

With that kind of value, diamonds need people, like Hatleberg.

The drawing that Hatleberg created of the facets of the Koh-i-Noor Diamond — which serves as his map to cutting the diamond.

“I protect diamonds," he says. "And people commission me to make a replica to protect their diamond whether it’s for insurance, security, display, promotion, historic documentation, education.”

He says people have made fakes for thousands of years. One of the first to commission a copy of the Hope Diamond was Napoleon III. Hatleberg is just continuing the craft. But what separates him is the quality of his goods. He once put one of his replicas next to the original and had a roomful of representatives from the famed diamond house, DeBeers, try to tell them apart.

They couldn’t. He’s that good.

His studio

Hatleberg lives directly across the street from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. His apartment is a museum of its own. His artwork fills his place, from gem paintings to pearl-encrusted corncobs. His dinning room walls are gold leafed. It’s… sensual.

“I love, I love paintings. I love gems. I love women. And I sometimes get them confused,” he admits.

Hatleberg's gem-cutting studio NEW

Credit: Courtesy of John Nels Hatleberg

The Baldichino table where Hatleberg cuts his gems and diamond replicas.

He works inside a tiny home studio. Research books stack like cairns on the floor. A photo gallery of his most famous diamond replicas stretches across one wall. In the far corner is a Baldichino, a table of sorts most commonly used to display statues of the Virgin Mary.

This is where he creates his replicas.

“And my premise for all the gems that I get to work with is I believe they are primal, living, and seductive.”

It takes months for Hatlberg to reverse-engineer a diamond. He won't disclose what he makes his replicas out of — let's just say the work is beyond intricate.

He sits at his facet machine, his diamond cutter, matching every angle of every cut. Hour after hour.

“I feel that I’m cutting the faces of people I know into the gem.”

The Smithsonian is working with him to create a new replica of the Hope Diamond. The museum says there’s really no one else on the planet who is able to match its distinct color perfectly. Soon, I would see in person what that means.

But while Hatleberg can talk on and on about his passion for diamonds, art, gems and women, he gets tight-lipped about the world of diamantaires, or leaders of the diamond industry. The people he does business with. All he’d tell me is this: it’s a small world made up almost entirely of men. There’s lots of discretion.

The vault

Hatleberg takes me to his vault at a secret location. Inside are Zip-Lock bags. Inside the bags are boxes. Inside the boxes are his most special gems. He wears cloth gloves to touch them. The first one he pulls out is an exact replica of the Koh-i-Noor Diamond.

“So this is the diamond that, at one point, was valued at half the value of the known goods of the world,” he says.

He lays two more gems next to it. Real ones. A blue topaz cut to resemble Michelangelo's design for the Campidoglio, and a purple amethyst with a cut inspired by contemporary architect Zaha Hadid.

All three sit together, representing different styles of gem cutting.

They sparkle in the light.

And as you stare at each one, you don’t want to stop. All are perfect to the eye.

And the longer you look, the more you forget that one of them is a fake.